(fig 1)

(fig 1)

Would you believe me, if I claimed that an algorithm which has been on the books as "optimal" for 46 years, which have been analyzed in excruciating detail by geniuses like Knuth and taught in all CS courses in the world, can be optimized to run ten times faster ?

A couple of years ago, I fell in interesting company, and became the author of an open source HTTP accelerator called "Varnish", basically a HTTP cache to put in front of slow web servers. Today Varnish is used by all sorts, from FaceBook, Wikia and SlashDot to obscure sites you have surely never heard about, many of which serve mostly pink bits, lots of pink bits.

Having spent 15 years as a lead developer of the FreeBSD kernel, I arrived in user-land with a detailed knowledge of what happens under the system-calls, and one of the main reasons I even accepted the Varnish proposal, was to show how to write a high-performance server program.

Because, not to mince words, the majority of you are doing that wrong.

Not just "wrong" as in "not perfect", but "wrong" as in "wasting half, or more, of your performance."

The first user of Varnish, the large Norwegian newspaper VG.no, replaced 12 machines running Squid with three machines running Varnish. The Squid machines were flat out 100% busy, while the Varnish machines had 90% of their CPU available for twiddling their digital thumbs[fn].

{[fn] This pun is included specifically to inspire Stan Kelly-Bootle}

The really short version of the story is that Varnish knows it is not running on the bare metal, but running under an operating system which provides a virtual memory based abstract machine.

For instance Varnish does not ignore the fact that memory is virtual, it actively exploits it. A 300GB backing store, memory mapped on a machine with 16GB or less RAM is quite typical. The user paid for 64bit of address-space, and I am not afraid to use it.

One particular task, inside Varnish, is expiring objects from the cache when their virtual life-timers run out of sand. This calls for a data structure which can efficiently deliver the smallest keyed object from the total set.

A quick browse of the mental catalog flipped up the "binary heap" card, which not only sports a O(log2(n)) transaction performance, but has a meta-data overhead of only a pointer to each object, which is important if you have 10M+ objects.

Careful re-reading of Knuth confirmed that this was the sensible choice, and the implementation was as trivial as always: "Ponto facto, Cæsar transit" &c.

On a recent trip by night-train to Amsterdam, my mind wandered, and it struck me, that Knuth might be terribly misleading on the performance of the binary heap, possibly even by an order of magnitude.

On the way home, also in the train, I wrote a simulation, which proved my hunch right.

Before any fundamentalist CS theoreticians choke on their coffee: Don't panic!

The P vs. NP situation is unchanged, and I have not found a systematic flaw in the quality of Knuths et al.'s reasoning. The findings of CS, as we know it, are still correct. They are just a lot less relevant and useful than you think. At least with respect to performance.

The oldest reference to the binary heap I have located, in a computer context, is J.W.J. Williams article in the 7th issue of Communications of the ACM titled "Algorithm number 232: Heapsort" from 1964[XXX: bib] [fn].

{[fn] How wonderful must it have been, to live and program back then, when all algorithms in the world could be enumerated in an 8 bit byte ?}

The trouble is, Williams was already out of touch and his algorithmic analysis was outdated, even before it was published.

In an article in the 4th issue of CACM J, Fotheringham documented how the ATLAS computer at Manchester University separated the concept of "an address" from "a memory location", which for all practical purposes marks the invention of Virtual Memory. [XXX: bib]

It took quite some time before Virtual Memory took hold, but today all general-purpose, most embedded, and many specialist operating systems use VM to present a standardized virtual machine model (ie: POSIX) to the processes they herd.

It would of course be unjust and unreasonable to blame Williams for not realizing that ATLAS had invalidated one of the tacit assumptions of his algorithm: only hindsight makes that observation possible.

But the fact that most CS educated professionals, 46 years later, still ignore VM as a matter of routine, is an embarrassment for CS as a discipline and profession, not to mention wasting enormous amounts of hardware and electricity.

Enough talk, let me put some simulated facts on the table:

(fig 1)

(fig 1)

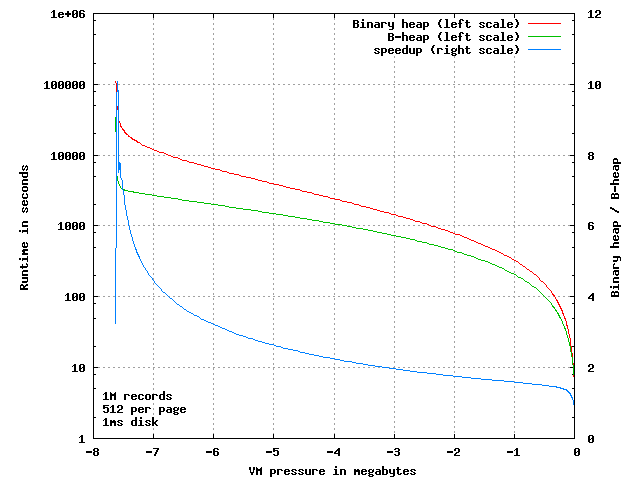

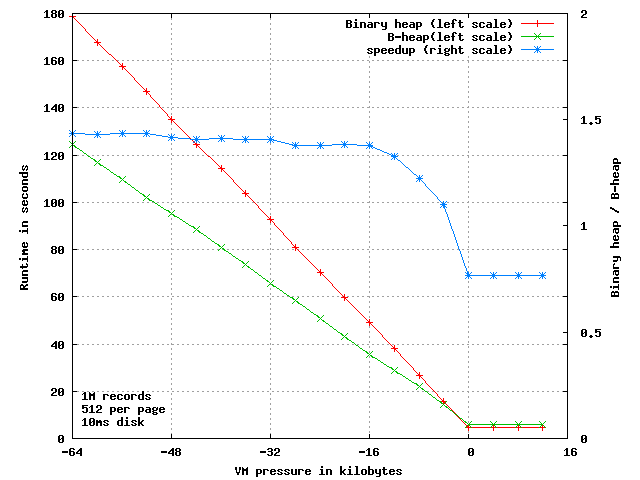

This plot shows the run-time of the binary heap and of my new "B Heap" version, for 1 million items on a 64bit machine[fn]

{[fn] Page-size is 4k each holding 512 pointers of 64 bits. The VM system is simulated with dirty tracking and perfect LRU page replacement. Paging operations set to 1 millisecond. Object key values are produced by random(3). The test inserts 1 million objects, then alternately removes and inserts objects 1 million times, and finally removes the remaining 1 million objects from the heap. Source code &c at http://phk.freebsd.dk/B-Heap/}

The X-axis is VM pressure, measured in the amount of address space not resident in primary memory, because the kernel paged it out to secondary storage. The left Y-axis is run-time in seconds (log-scale) and the right Y-axis shows the ratio of the two run-times: (binary heap / B-heap)

Lets get my "order of magnitude" claim out of the way:

(fig 2)

(fig 2)

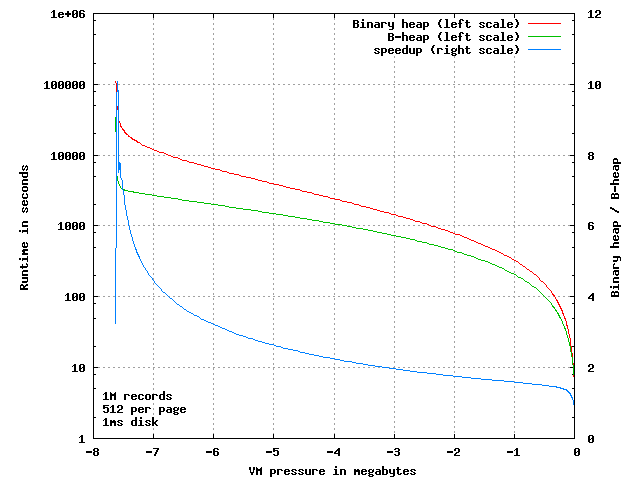

When we zoom in on the left side, we see that there is indeed a factor 10 difference in the time the two algorithms take, when running under almost total VM pressure: only 8 to 10 pages of the 1954 pages allocated are in primary memory at the same time.

Did you just decide that my order of magnitude claim was bogus, because it is only based on an extreme corner case ?

If so, you are doing it wrong, because this is pretty much the real-world behavior seen.

Creating and expiring objects in Varnish is relatively infrequent actions. Once created, objects are often cached for weeks if not months, and therefore the binary heap may not even be updated once per minute, on some sites not even once per hour.

In the meantime we deliver gigabytes of objects to clients browsers, and since all these objects compete for space in the primary memory, the VM pages containing the binheap which are not accessed get paged out.

In the worst case of only 9 pages resident, the binary heap averages 11.5 page transfers per operation, the B-heap only needs 1.14 page transfers.

If your server has SSD disks, that is the difference between each operation taking 11 or only 1.1 milliseconds. If you still have rotating platters, it is the difference between 110 and 11 milliseconds.

A this point, it is wrong to think "If it only runs once per minute, who cares, even if it takes a full second ?"

We do in fact care, because the 10 extra pages needed once per minute, loiters in RAM for a while, doing nothing for their keep -- until the kernel pages them back out again.

...at which point they get to pile on top of the already frantic disk activity, typically seen on a system under this heavy VM pressure[fn].

{[fn] Please don't take my word for it: Applying queuing theory to this situation is a very educational experience.}

Next, let us zoom in on the other end of the plot:

(fig 3)

(fig 3)

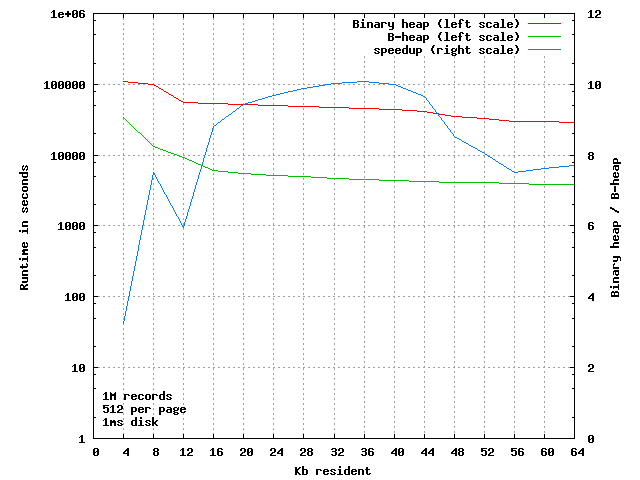

If there is no VM pressure, the B Heap algorithm needs more comparisons than the binary sort, and the simple parent-to-child / child-to-parent index calculation is a tad more involved, so instead of a run-time of 4.55 seconds it takes 5.92 seconds, a whopping 30% slower, almost 350 nanoseconds slower per operation.

So yes: Knuth and all the other CS dudes had their math figured out right.

But if we move left on the curve we find, at a VM pressure of four missing pages (= 0.2%), the B-heap catches up, due to fewer VM page faults, and it gradually gets better and better, until as we saw above, it peaks at 10 times faster.

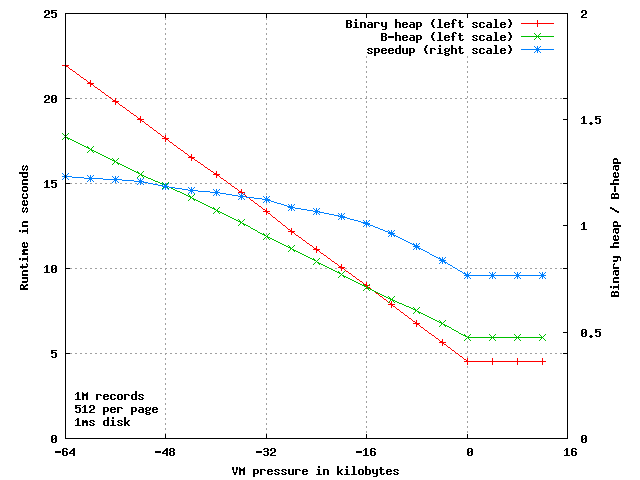

That was assuming you were using a SSD disk, which can do a page operation in 1 millisecond, which is pretty optimistic, in particular for the writes. If we simulate a mechanical disk, by setting the I/O time to a still optimistic 10 milliseconds instead:

(fig 4)

(fig 4)

Now B-heap is 10% faster as soon as the kernel steals just one single page from our 1954 page working set and 37% faster when four pages are missing.

The only difference between a binary heap and a B-heap is the formula for finding the parent from the child or vice versa.

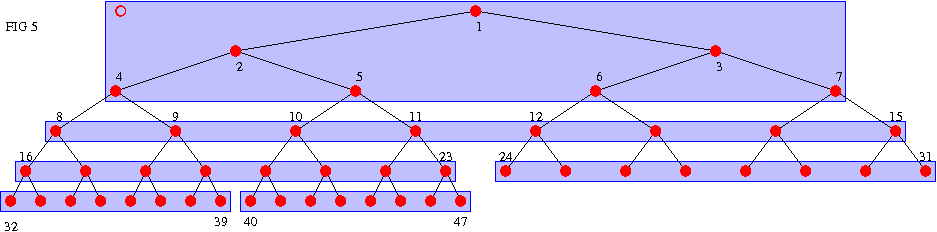

The traditional n -> {2n, 2n+1} formula leaves us with a heap built of virtual pages stacked one over the next, which causes (almost) all vertical traversals to hit a different VM page for each step up or down in the tree, as shown in figure 5, with 8 items per page:

(fig 5)

(fig 5)

(The numbers show the order in which objects are allocated, not the key values)

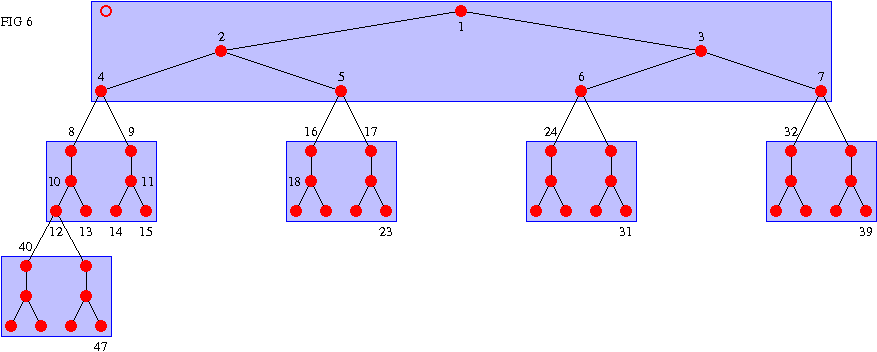

The B-Heap builds the tree by filling pages vertically, to match the direction we traverse the heap:

(fig 6)

(fig 6)

This rearrangement increases the average number of comparison/swap operations required to keep the tree invariant true, but ensures that most of those comparisons happen inside a single VM page, and thus reduces the VM footprint and consequently VM page faults.

Two details are worth noting:

Once we leave a VM page through the bottom, it is important for performance that both child nodes live in the same VM page, because we are going to compare them both to their parent.

Because of this, the tree fails to expand for one generation, every time it enters a new VM page, in order to use the first two elements in the page productively.

In our simulated example above, failure to do so would require 5 pages more.

If that seems unimportant to you, you are doing it wrong: Try shifting the B-Heap line 20kB to the right in figure 2 and three above, and think about the implications.

The parameters of my simulation are chosen to represent of what happens in real life in Varnish, and I have not attempted to comprehensively characterize or analyze the performance of the B-heap for all possible parameters.

Likewise, I will not rule out that there are smarter ways to add VM-clue to a binary heap, but I am not inclined to buy a ticket to the Trans-Siberian in order to find time to work it out.

The order of magnitude difference obviously originates with the number of levels of heap inside each VM page, so the ultimate speedup will be on machines with small pointer sizes and big page sizes, a very pertinent observation, as OS-kernels start to use superpages to keep up with increased I/O throughputs.

My esteemed FreeBSD colleague Colin Percival helpfully pointed out, that the change I have made to the binary heap is very much parallel to the change from binary tree to B-tree, so I have adopted his suggestion and named my new variant a "B-heap"[fn]

{[fn] Does CACM still enumerate algorithms, and is 8 bits still enough ?}

There used to be an (in)famous debate: "Quicksort vs. Heapsort", centering on the fact that the worst case behavior of the former is terrible, whereas the latter has worse average performance but no such "bad spots". Depending on your application, that can be a very important difference.

But we lack a similar inquiry into algorithm selection in the face of the anisotropic memory access delay, caused by virtual memory, CPU caches, write buffers and other facts of modern hardware.

Whatever book you learned programming from, it probably had a figure within the first 5 pages, showing a computer as consisting of:

MEMORY ---- CPU ---- I/O

(fig 7)

That is where it all went pear-shaped: that model is totally bogus today.

But it is, amazingly, the only conceptual model used in computer education, despite the fact that it has next to nothing to do with the execution environment on a modern computer.

And just for the record: by "modern" I mean "VAX 11/780 or later."

The last 30-40 years of hardware and operating systems development seems to have only marginally impinged on the agenda in CS departments algorithmic analysis section, and as far as my anecdotal evidence, it has totally failed to register in the education they provide.

The speed disparity between primary and secondary storage on the ATLAS computer were on the order of 1:1000. The ATLAS drum took 2 milliseconds to deliver a sector, instructions took approx 2 microseconds to execute. You lost around 1000 instructions for each VM page fault.

On a modern multi-issue CPU, running at some gigahertz clock frequency, the worst case loss is almost 10 million instructions per VM page fault. If you are running with a rotating disk, the number is more like 100 million instructions[fn].

{[fn] And below the waterline there are the flushing of pipelines, now useless, and in the way, cache content, page table updates, look-a-side buffer invalidations, page table loads c. &c. It is not atypical to find instructions in the "for operating system programmers" section of the CPU databook, which take hundreds or even thousands of clock-cycles, before everything is said and done.}

What good is an O(log2(n)) algorithm, if those operations cause page faults and slow disk operations ? For most relevant datasets an O(n) or even an O(n^2) algorithm, which avoids page faults, will run circles around it.

Performance analysis of algorithms will always be a (the ?) cornerstone achievement of Computer Science, and like all of you, I really cherish the fold-out chart with the tape-sorts in volume 3 of The Art of Computer Programming.

But the results coming out of the CS department would so much more interesting and useful, if they applied to real computers and not just toys like ZX-81, C-64 and TRS-80.

Poul-Henning Kamp

$Id: queue.html,v 1.15 2010/05/14 21:10:49 phk Exp $